The increasing user-friendliness and pervasion of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) tools are resulting in an exponential leap of malicious multimedia content online. Democratization of the ability to distort reality using generative AI applications and to spread fake content on social media channels have put deepfake technology under scanner worldwide. With every passing day, the increasing sophistication of ML techniques in distorting images and videos is making deepfakes more realistic and highly resistant to detection. The rapid diffusion of spurious content in social networks poses an imminent risk of endangering the social, political, and economic stability of a country, which can further compromise the sovereignty and security of the state. This results from the toxic manner in which networked information platforms interact with our cognitive biases. Despite the benefits that generative AI-enabled deepfake technology brings, the impending concerns merit an investigation, especially regarding the role of deepfake technology and synthetic media in radicalizing the youth through the diffusion of disinformation in offline and online youth networks.

The study of the impact of deepfakes and synthetic media on youth’s perception of reality warrants attention because, if left unchallenged, synthetic media can have profound implications for the sovereignty of a nation, security of citizens, journalism, democratic fabric, and trust in the world wide web. The authenticity of the entire online political discourse stands at the risk of collapse, which can potentially have far-reaching ramifications on the economic and social environment of a country. Therefore, investigating the network effects in the dissemination of deepfakes and identifying technological solutions to mitigate the publication of synthetic media online bears significance for the safety of digital natives and network information platforms.

1.1. Research objectives and research questions

The paper aims to provide an in-depth assessment of the causes and consequences behind the spread of disinformation among youth via deepfake technology and to examine the influence of echo chambers and social media algorithms on the exposure of youth to disinformation. The research also delves into youth perception and trust in digital content and explores the existing and potential tools for responding to malicious synthetic media. Through anonymous primary research conducted with participants across the world, the author investigates the susceptibility of youth to radicalization, while supporting the insights using case studies of deepfake-fueled disinformation campaigns. Finally, the paper recommends a multistakeholder approach to combating the issues related to deepfakes and elucidates the responsibilities of technology companies and social media platforms in curbing disinformation-led radicalization.

1.2. Definition of key terms

- Generative AI: Algorithms that are capable of generating text, images, or other multimedia using generative models, that learn the patterns and structure of their input training data to generate an output that bears similar characteristics.

- Synthetic media: Artificial production, manipulation, and modification of data and media using automated AI algorithms.

- Deepfakes: Synthetic media – image, audio, or video – that have been digitally manipulated using an algorithm to substitute one person’s physical characteristics convincingly with someone else.

- Radicalization: Process by which an individual or a group of individuals adopt violent extremist ideologies against a particular group of people.

- Disinformation: False information spread covertly and deliberately, intending to mislead and influence public opinion and to obscure truth.

- Literature Review

A significant volume of research exists on the factors that drive disinformation among the youth and the role of disinformation in radicalizing the youth. The subject of Generative AI and its association with disinformation has been of interest to researchers recently and we hereby explore online radicalization trends due to disinformation among the youth.

2.1. Online radicalization trends among youth

Exposure to radicalization has been increasing for the youth on online platforms. The depiction of radicalized groups as desirable and the network effects that help in the fast propagation of hate speech on social media platforms have increased the threat of extremism among the youth. The uninterrupted connection of the youth and children to the internet has led extremist groups to run recruitment drives online, by portraying extremism as a superior ideology. For example, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) has leveraged age-appropriated, curated content and platforms to entice the 1 billion Muslims under the age of 30 globally towards their violent ideologies. Influenced by the radicalization attempts by ISIS, three schoolgirls in London traveled to Syria to join the militant organization. A similar example appeared in the United States in 2020, in which a 17-year-old Midwesterner led the recruitment of a cell for attacking power lines in the wake of Donald Trump’s loss in elections [2]. A 13-year-old Estonian boy, posing as leader commander of the extremist group ‘Feuerkrieg Division’, propagated extremist content using the Telegram app to call for terrorism with pro-Nazi motives. A British far-right activist group, called Patriotic Alternative, has done a nine-part livestream series named ‘Talking with Teens’ which shows interviews of far-right teenagers [6].

A lack of moderation on instant messaging apps, such as Telegram, and on multimedia sharing platforms, such as YouTube and Instagram has made the internet a fertile ground for the emergence of explicitly radical groups in Europe, North America, and Asia. The internet has become an active vector for violent radicalizations facilitating the proliferation of extremist ideologies in fast, decentralized, low-cost cost, and largely unmoderated global networks. Internet and social media shift the public from passive and active agents who gather information independently, instead of waiting for organizations to authenticate, filter and deliver it [1]. Online chatrooms have the potential to facilitate networking among followers of the same ideology through discussion forums, reinforce personal relationships, and offer information about extremist actions, though the role of chatrooms in coordinating attacks is not evident in existing literature yet.

Internet use by extremist groups is primarily focused on psychological warfare, propaganda, fundraising, data mining, and recruitment and mobilization [7]. Social media groups allow people to isolate themselves in an ideological niche by seeking and consuming information that validates their views, thereby strengthening Confirmation Bias. The fragmentation of online platforms into such specific niche groups makes it difficult to detect and address challenges posed by extremist groups operating silently in online networks. A scarce amount of empirical research exists on the influence of disinformation on actual political violence, and hardly any on its connection to terrorism specifically. The governments that tend to circulate disinformation and propaganda online through their or foreign governments’ social media channels are subject to higher levels of domestic terrorism. Whereas, the deliberate dissemination of disinformation online by political actors increases the political polarization of the country [8].

An interesting insight comes from communication scholar, Archetti who stated in 2013 that the mere existence of propaganda material online should not be equated to the magnitude of consumption by the audience and its influence on the audience [3]. Research by Pauwels and Schils also found the same through their research with 6,020 respondents in 2016. However, what is intriguing to note is the length to which the extremists go to form an interpersonal connection with their audience. This becomes evident with the growing presence of radicalized women online and the use of women by specific religious extremist groups to influence and recruit more women by building an interpersonal connections [1].

2.2. Role of disinformation in radicalization processes

European Union describes ‘disinformation’ as “verifiably false or misleading information that is created, presented and disseminated for economic gain or to intentionally deceive the public and may cause public harm”. A report by the independent High-Level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation, published in 2018, also adopted a similar definition. Colomina et al. in their report published with the European Parliament in 2022 argued that production and promotion of disinformation can be driven by a variety of factors, including reputational goals, economic factors, and political agendas. The reception, engagement, and amplification of disinformation are intensified by different audiences and communities [9]. Nasar and Akram (2023) found that individual users’ political interests served as key factors in their radicalization, such as citizens losing faith in the government and political parties [10]. Disinformation uses unethical persuasion techniques, or propaganda, to generate insecurity, tearing cohesion, or inciting hostility [11]. Disinformation eventually leads to the erosion of trust and credibility of democratic processes, as mentioned in the European Commission’s strategy Shaping Europe’s Digital Future [12]. Resolution 2326 (2020) of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe expresses concern about the scale of disinformation campaigns that aim to influence public opinion and increasingly polarize the masses [9]. Resolution 2217 (2018) of the Council defines “fake news” as a form of “mass disinformation campaigns”, constituting a technique of a “hybrid war”. Significant literature has been produced by international organizations on the disinformation acting as a driving factor behind radicalization.

2.3. Impact of Generative AI-fueled deepfakes and synthetic media in the digital landscape

Despite Generative AI having caught the attention of the industry largely in 2023 because of the emergence of ChatGPT, literature on Generative AI and deepfakes had emerged years earlier. McGuffie and Newhouse authored a paper in 2020 on the radicalization risks posed by GPT-3 developed by OpenAI in the same year. The report cited the research conducted by the Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism (CTEC) on GPT-3 to evaluate the scope of weaponization of unregulated large language models at the hands of extremist groups. While the report argued for the safety of GPT-3 algorithms used by OpenAI, it raised concerns about unregulated duplicate technologies that can aid large-scale online radicalization and recruitment [15]. However, concerns do exist about GPT-3 producing radical content if it is supplied with tweets, paragraphs, and forum threads that help GPT-3 develop a pattern that produces fake news and spreads disinformation. McGuffie and Newhouse discovered that GPT-3 could be exploited in 2020 to produce fake forum threads casually discussing genocide, promote Nazism, create extremist viewpoints in its answers, and produce multilingual extremist text [15].

International research organizations have written about the risks deepfakes pose to the democratic stability of nations and the balance of power in geopolitics. Realistic videos of politicians burning holy books, of leaders surrendering their sovereignty, and of sowing confusion in diplomatic circles have already emerged in several instances recently [14]. Karnouskos (2020) gave various perspectives to analyze the impact of AI in digital media. While the “Media Production” perspective highlights the constructive use cases of synthetic media in automating the generation of personalized marketing content, the “Media and Society” perspective raises concern over the lack of regulatory policies around synthetic media. Generative AI enables people to visualize artificially created characters not conventionally as metallic robots but as entities displaying the same emotions, values, and linguistic skills as the consumer of deepfake content [13].

- Mechanism of Online Radicalization

An investigation into how the youth becomes susceptible to online hate and radicalization requires comprehension of the factors that drive the adoption of extremist ideologies by the youth. The process of radicalization is continuous, reinforcing, and emotionally charged, which aims at influencing a mindset shift in the consumer. Extremist organizations generally target the youth with their toxic content, which is followed by other multimedia content carrying the same sentiment. Eventually, the targeted youth begin to feel a sense of deep connection to the ethos of the piece of disinformation and this leads to radicalization.

3.1. Key factors contributing to the susceptibility of youth to radicalization

Understanding the psychology of the youth and their online behavior is critical and a precursor to the process of identifying how Generative AI-fueled deepfakes influence them. Koehler (2014) provides deep insights into the psychology behind extremist online behavior by the youth. Despite his research methodology being based entirely on interviews with German right-wing activists, the research outcomes are largely applicable to youth across diverse geographies, who consume internet services and engage in the creation and dissemination of radical viewpoints.

Network effects: The one-way network effect created by the internet encourages the participation of the youth in extremist discourses online. The Internet provides a cost-effective and effective platform to communicate and bond with like-minded individuals across geographical borders [16]. The ease of networking and the simplification of communication facilitated by the internet make it easier for the susceptible youth to find a group they can resonate with.

Anonymity: The perception of an unconstrained space of anonymity motivates individuals to be more vocal about radical sentiments online than they would usually be offline. A lack of censorship on what an individual can write or post in online forums also gives them additional confidence, alongside the instant essential affirmation they may get from responses of other like-minded individuals. This sense of privacy has been observed to prompt introverted individuals to act like pure agitators online. Moreover, the administrators of chat rooms dealing with radicalizing disinformation were found to be more concerned with privacy, encryption, and data security [16].

No fear of exclusion: Interviewees in Koehler’s research also highlighted how the internet gave them a core sense of freedom to live their ideology and propagate it through non-political activities without the fear of social resistance. Such a feeling of safety builds confidence and affirms one’s commitment to a particular ideology.

Easier propagation of ideology: Extremists tend to cling to rhetoric that supports and amplifies their beliefs despite counter-rhetoric available in society. Support of such ideologies by political factions adds a layer of legitimacy and credibility to such radical philosophies and eventually, creates a sense of superiority of one ideological group over another, thereby fueling discord [17].

Perception of critical mass: The Internet provides a platform for ideological advancement through potentially unlimited participants in theoretical discussions on extremist topics. Anyone can create their school of thought based on subjective interpretations and influence their online movement. The perception of a critical mass within such movements motivates the youth to act more radically to indoctrinate other participants in the ecosystem and to derive a misplaced feeling of leadership online [16].

Studies by Garry et al. show that individuals who are highly susceptible to violent extremism often display a lack of self-worth, self-esteem, and sense of belonging. The inability to find a sense of belonging in one’s family, community, or environment can lead some young people to find the same in extremist organizations or online hate groups. Self-uncertainty can lead people to develop strong attitudes towards social issues and find a solution to extremism [17].

Two psychological phenomena that lead to the escalation of radicalization among the youth in online platforms are “Group Polarization” and “Groupthink”. Group polarization refers to the tendencies of a group of people to make and affirm decisions based on the mindset other people in a group are displaying or are believed to be displaying. Groupthink refers to the phenomenon where people in a group make decisions and behave in ways different from their normal behavior, to fit in a group. While group polarization emboldens ideologies through immersion in a community of like-minded individuals, groupthink results in a loss of ability to think of alternative perspectives and counternarratives [17]. This eventually leads to the loss of autonomy of an individual and the emergence of groupism.

An act of sharing text messages, images, videos, etc. on social media platforms needs to be viewed as a matter of trust. The youth is more inclined to trust the information shared by friends, relatives, and people in close networks. This leads to swift sharing of information by the youth without checking the veracity of the content. A study at Columbia University in 2019 showed that 59% of the links that had been shared in social media as part of the study had not been previously read because users were found to be in the habit of viewing attractive or provocative multimedia content and sharing it on the impulse of intriguing content. A separate study by Middaugh in 2019 showed that language that seeks to elicit strong emotional responses using out-of-context, misleading generalizations also leads to the impulse sharing of spurious information by people. The youth is particularly vulnerable to such provocative language and somehow deactivates the mechanism of defensive reasoning when their published posts receive positive feedback [18]. A study by Comenius University in 2022 showed that only 41% of teenagers could tell the difference between genuine and fake online health messages. 41% of participants in the study considered genuine and fake news to be equally trustworthy [19].

The concern gets exacerbated by the “digital native” generation, which has grown up in a multiscreen society and may consider digital technology an integral part of their existence. The disconnect between the offline world and genuine, verified news in the newspapers aggravates the issue of disinformation-led youth radicalization. Moreover, the tendency to consume news corresponding to one’s momentary beliefs and attitude leads to selective exposure of the youth to disinformation. Moreover, the attention of the youth to news articles is minimal, which further impairs their ability to distinguish between genuine and fake news [20].

From a psycho-linguistic perspective, radical hoaxes have the potential to become a means of conveying stereotypes and prejudicial falsehoods through the manipulation of language [20]. The inability of the youth to discern manipulative language can result in the formation of trust in the spurious piece of information, which further amplifies the problem of online radicalization if the information is shared without verifying it with other sources.

3.2. Role of echo chambers and filter bubbles in fostering radical ideologies

Social media algorithms facilitate a user’s intent and ability to interact with like-minded individuals and in some ways, encapsulate the user in a space where diversity of opinions is filtered out. The algorithms’ tendency to limit a user’s exposure to diverse viewpoints bears the potential to encourage the adoption of extreme ideological positions. This is due to the exposure of users to congenial, opinion-reinforcing content while excluding more diverse, perspective-challenging content [21]. The selective exposure theory predicts that users of social media prefer to consume information that reinforces their opinions, rather than consuming the ones that challenge their strongly held viewpoints. Garrett’s study in 2009 through interviews with 727 online news consumers showed that individuals display a higher preference for reading news aligned with their ideologies and express disinterest in consuming news that challenges their existing outlook [21]. This is enabled by the personalization algorithms which are sensitive to personal preferences of social media users and filter out information that does not align with the narrower category of content.

This leads to the emergence of what experts call “echo chambers” and “filter bubbles”. Echo chambers are virtual communities in which members receive and share information that conforms to their beliefs and ideologies. Filter bubbles refer to the online groups that receive information from the platform filtered according to the ideologies they subscribe to in their online realm. In other words, echo chambers are the result of users’ self-selection of information sources, whereas filter bubbles are the result of an algorithm making those selections. Both lead to the narrowing of topics and perspectives that a user is exposed to.

Research by Lawrence et al. in 2010 found that the readers of political blogs are more ideologically segregated and more ideologically opinionated, compared to the non-readers [22]. A similar finding was made by Wojcieszak and Mutz in 2009 who found participants in online politics-related groups to be less exposed to political information that was non-conformant with their opinions, compared to those who were part of non-political online forums [23]. Group polarization occurs in such echo chambers because of individual and collective adoption of radical viewpoints through intensive deliberations by small groups of homogenous individuals. The confinement of the youth inside the filter bubbles leads to their social isolation in the physical world, and increased socialization in the polarized echo chambers.

However, empirical evidence about the influence of social media and other digital platforms on the information consumption pattern of the youth is still inconclusive. Evidence exists to show that individuals and groups that harbor extremist opinions may also purposely seek out ideologically discordant information online to gain an understanding of opposing viewpoints. However, they remain antagonistic to the opposing viewpoints, which leads to a condition called “affective polarization” [21]. Gao et al. (2023) explored the effects of echo chambers on short video platforms, such as TikTok, YouTube, and others. The tendency of homophily was found to be increased on such platforms due to the selective exposure to information provided by echo chambers and filter bubbles [24].

3.3. Social media algorithms-led disinformation

Filter bubbles work based on how algorithms segregate information into various categories and feed information to the users based on their ideological inclinations, thereby reinforcing their preconceived notions. Search platform algorithms and social media algorithms usually check for which links and hashtags you click on most frequently and which type of information you engage with most in terms of reading time, reactions, comments, and sharing. This helps the algorithms to collate the behavior or response of a large pool of users to the information presented to them, based on which the algorithms predict the relevance of future results. This phenomenon called “relevance feedback” helps algorithms to understand the ideology and preferences of a user, particularly the youth, and create a stereotype about them. The higher the click-through rate of a link in your feed, the higher the probability of similar posts showing up in your search results and social media feed.

User engagement globally with different kinds of information also influences the type of information that is displayed to a specific individual in the search results or social media feed. Therefore, the information selected and presented by an algorithm to an individual is a function of the individual’s search and engagement history and engagement of other users worldwide with online content. Internet users are susceptible to provocative and sensational news stories, which increases the engagement rate of such dubious information and therefore, they get pushed up in the search query results of a search engine [25]. This leads to an even greater engagement rate for the sensational news piece which eventually propagates disinformation online.

Research by The Conversation in 2018 showed that the more people searched for a topic, the higher Google pushed that topic up in its search results. In this study, people picked sensational headlines or fake news over trustworthy information more than half of the time, which demonstrated how human thought patterns are lenient towards provocative information, which further influences the algorithms [25].

Multilingualism of disinformation on social media also poses a threat. Algorithms trained on detecting hate speech in the English language may not work effectively in non-English languages. In 2020, researchers at Facebook (now Meta) admitted that the company had fallen short of curbing hate speech in the Arabic world. Only 6% of the Arabic-language hate content was detected on Instagram, compared to a 40% takedown rate on Facebook. Parallelly, advertisements attacking the LGBTQ+ community were rarely flagged for removal in the Middle East, whereas non-violent content was incorrectly deleted 77% of the time, affecting people’s ability to express themselves online [26]. Recommendation algorithms in social media platforms tend to amplify disinformation among the youth, especially through echo chambers, by nudging the users to consume content that has had a higher engagement rate despite no assurance of the veracity of the information presented.

A major concern with disinformation over social media is the multimodal data, that exists in the form of images, memes, and videos), which cannot be effectively processed by text analysis solutions. Misleading visual information can elicit emotions, attitudes, and responses from consumers that can lead to radicalization. Scientific research on visual disinformation is still in its infancy [27]. The ease of access to tools that can create synthetic media and post it on social media channels without moderation is also fueling disinformation.

- Generative AI, Deepfakes, and Synthetic Media in the Disinformation Ecosystem

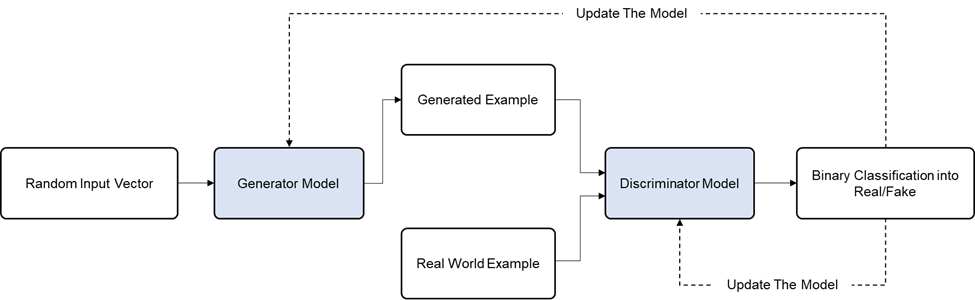

The world has not been more rattled by AI before than it has been since the democratization of Generative AI tools online. Based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN), Generative AI models use neural networks to identify the structures and patterns within existing data to generate new and unique content. The training process for a generative AI model begins with a large dataset of audiovisual examples [28]. The model analyzes the structures and relationships in the input data to identify the underlying rules governing the content. Next, it generates new data by sampling from a probability distribution that it has learned. This first output can be quite different from the training dataset. Finally, the generative AI model continuously adjusts its parameters to maximize the probability of similarity between output and training data. This final step of refining the output continuously is called “inference” [28].

Generative AI models use two neural networks – a discriminator and a generator. The discriminator is responsible for recognizing patterns in datasets and using them to make predictions or classifications about new samples. It distinguishes a sample from the training dataset and either accepts or rejects an AI model output depending on how similar it is to the genuine samples provided in the training dataset. The generator is entrusted with using the underlying patterns in training datasets to create new samples, which are similar but not identical to the original dataset. Generators can use both semi-supervised algorithms (which are dependent on labeled datasets) and unsupervised algorithms (based on unlabeled datasets). The generator takes a random input vector and uses it to create a new image based on the inputs given by the user and the training dataset. The initial output looks like random pixels and the discriminator compares this output with the original dataset to classify the generator output as original or fake. The first few outputs of the generator are well-detected as fake by the discriminator. Using this methodology, the discriminator gets better at discriminating fake images from genuine ones, while the generator gets better at narrowing the gap between its output and original genuine images. In other words, the discriminator and the generator treat each other as adversaries, which gives name to Generative Adversarial Networks. The process ends when the discriminator finds almost no difference between the original dataset and the generator’s output.

Figure 1 shows the process used by Generative Adversarial Networks to create output that is similar to the original dataset.

Fig. 1: Generative AI working mechanism

4.1. Generative AI-fueled synthetic media-driven disinformation

Deepfakes – a portmanteau of “deep learning” and “fake media” – is a type of synthetic media invented in 2017. Since then, the deepfake technology has been primarily used for unethical purposes, with the most prevalent (over 95%) type of deepfake videos being pornographic. Miscreants use manipulated pornographic images of an individual for extortion, cyberstalking, blackmailing, and digital trafficking, i.e., making money by selling immodest images of an individual online. The use of deepfakes has also entered the political sector [30]. In 2018, a deepfake video of the then-United States President, Barack Obama was released by Jordan Peele in collaboration with Buzzfeed. Though the content of the video was harmless, it highlighted how a deepfake video could be easily created using generative AI technology to spread any message according to the will and intent of the creator.

Recently, manipulated videos of politicians and world leaders have emerged which intend to put the leaders in poor light and tarnish their reputation. A few deepfake videos that have emerged in 2022 and 2023 also bear the potential to create an imbalance in global geopolitics. For example, a video of Russian President, Vladimir Putin emerged in June 2023 during the Ukrainian-Russia war where Putin could be seen declaring a full-scale military mobilization to attack Ukraine. Similarly, a deepfake video had surfaced around the same time showing Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy surrendering his country’s position in the war. Such deepfake videos stand to grow more sophisticated in the future, which can make their detection difficult and therefore, can disrupt the political stability of the concerned nation(s) and can influence the geopolitics of the neighborhood region.

Synthetic media-driven disinformation assumes a more dangerous proportion if used for spreading propaganda. A publication by the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute describes deepfakes as a means for terrorist organizations and anti-national elements to spread deepfake-led disinformation, aimed at “manipulating public opinion and undermining people’s confidence in state institutions” [5]. However, deepfakes by terrorists are less visible and accessible to the general public. A greater risk is posed by the deepfakes that are created using politicians’ facial information. Synthetic media of politicians, such as audio, images, and videos, showing offensive remarks against a particular community can create outrage and influence sympathizers, which can lead to riots, demonstrations, and the breakdown of the political structure of a nation. Using deepfake, a voice can also be created for the generated avatar to sound like the original speaker [30]. Deepfakes have a significant impact on the ability of individuals to determine the origination, credibility, quality, and freedom of information. Such macro effects amplify the potential value of deepfake content among belligerent actors new opportunities for enhancing attempts at disinformation and coercion [29].

Deepfakes can have a more dangerous consequence if used and approved for political propaganda by the political actors themselves. For example, a national political party in India had used a deepfake of its leader to spread a harmless message [31]. However, it portrayed the national party – which was also in power – as an endorser of synthetic media, thereby leading to questions being raised on India’s commitment to mitigating synthetic media-fueled disinformation. The video of the politician went viral on the instant messaging platform, WhatsApp, showing how fast could fake videos travel among the citizens on an unmoderated platform. Pro-China campaigns using deepfake videos of journalists have also been disseminated over social media channels to promote the interests of the political party in power [32], showing how disinformation can be state-sponsored, which makes it difficult to mitigate.

4.2. Case studies of deepfake-fueled disinformation affecting political stability

Various incidents have emerged since 2019 where deepfakes have been used to radicalize the youth and disturb political stability. One such example emerged in March 2023, when a deepfake photo of Wikileaks founder, Julian Assange, emerged showing him suffering in prison. This led to outrage by people who could not identify it as a fake image until a German newspaper revealed that it was a deepfake created by an individual in protest of the treatment meted out to Assange. In the same month, an AI-manipulated image of former United States president, Donald Trump getting arrested was shared on social media, showing how susceptible people are on online platforms [33].

In May 2023, an AI-generated synthetic image of the bombing of the Pentagon went viral on social media platforms. Though the fake image did not radicalize the youth, the S&P 500 stock index fell 30 points in minutes, leading to USD 500 billion wiped off its market capitalization [33]. Despite the markets rebounding after the image was declared as deepfake, it showed how synthetic media can disrupt the economic and political stability of a country, and also highlighted the inefficacy of social media platforms in detecting and removing such fake content.

In 2019, a deepfake video president of Gabon, Ali Bongo surfaced and triggered a coup, despite him having not made an appearance in public for several months [35]. The use of AI-generated deepfakes to commit crimes has been increasing. Sumsub – a company in the financial services sector – released data for 2022-23 that showed deepfake-related fraud cases had increased from 0.2% in the first quarter of 2022 to 2.6% in the first quarter of 2023 for the United States, and from 0.1% to 4.6% in Canada over the same period [34]. This highlights the rise of the adoption of deepfake content creators and the far-reaching implications it can have.

4.3. Challenges in detection of deepfakes

The increasing sophistication of the generator models is resulting in growing difficulty in the detection of deepfake videos and images. Accuracy of deepfake detection has been a point of contention among experts for a few years and it is becoming nearly impossible to differentiate between genuine and fake videos online [36]. Neekhara and Hussain from the University of California San Diego presented a new technique in 2021 that renders a deepfake video foolproof to the discriminator models. Insertion of slightly manipulated inputs, called “adversarial examples”, into each frame of a deepfake video makes it difficult for the detection algorithm to identify the signs of synthetic media. These adversarial inputs exploit a vulnerability in the detection models, which helps the deepfake bypass the detection process as a genuine video. The success rate of deepfake videos bypassing detection in their research was above 90%, because of the imperceptible adversarial perturbation in each frame [37].

Detection of deepfake videos depends on several factors, including image resolution, level of compression, and composition of the test set. In 2019, Rössler et al conducted a comparative analysis of the performance of seven state-of-the-art deepfake video detectors using five public datasets and found the range of accuracy to be spread between 30% and 97% [39]. None of the detectors were found to be reliable for all types of deepfakes. This is because different detectors are tuned to identify a certain type of manipulation using training datasets and when they operate on novel data, the performance reduces [38]. The advancement in detection methods is currently surpassed by the generative frameworks, which is increasing the gap between the effectiveness of discriminator and generator models.

Most of the deepfake videos produced today are largely static, in the sense that they depict stationary objects with unchanging environments and lighting. The currently available detection methods are trained on such static deepfake videos. However, adversarial networks would soon extend the synthetic media techniques to generate dynamic videos, with changing lighting, background, and pose of the deepfake character. The dynamic attributes will make it more challenging for detection methods to identify a deepfake [40]. Moreover, such dynamism will make the videos look more genuine to the human eyes, making deepfake avoidance more challenging.

An individual’s psychological response to deepfakes also warrants inspection, because most of the time during the consumption of synthetic media, individuals do not have advanced detection models at their disposal. Research by Batailler et al. in 2022 showed that partisan bias can lead people to believe in videos and images that present information congruent to their beliefs while ignoring incongruent information. Moreover, prior exposure to fake content increases the risk of individuals believing in other fake information. And finally, cognitive reflection studies show that inattentiveness and lack of critical thinking largely drive belief in synthetic information [41]. However, it is interesting to note that exposure to information explicitly classified as deepfake leads to a notion of “liar’s dividend”, which makes an individual doubt even genuine information because of increased skepticism towards online media [40], which leads to a trust deficit in the online ecosystem.

- Impact of Deepfakes on Youth Perception and Trust in Digital Content

Considering how the psychology of the youth works and how generative AI-fueled deepfakes are inching closer to indistinct reality, the adage “seeing is believing” no longer holds relevance. Understanding the power of visual communication is crucial to analyzing the influence of deepfakes on the perception of and trust in digital content among the youth. Research by Graber (1990) found that television viewers were more likely to recollect visual information compared to verbal information with higher accuracy [43]. Grabe and Bucy (2009) also demonstrated that image clips of political leaders were more influential in shaping the perception of the voters compared to audio information [42]. Misleading visual content is more likely to be misleading than any other form of content to generate false perceptions about politicians, leaders, institutions, and events. Stenberg (2006) found the “picture superiority effect”, which refers to the phenomenon of people retaining better memory for pictures than for corresponding words, has been variously ascribed to a conceptual or a perceptual processing advantage [44]. As a result, AI-generated text may have a lower impact on people compared to the visual content. Witten and Knudsen (2005) argued that the perceived precision is higher for visual information, which helps it to get integrated more effectively with other types of sensory data [45].

The ease of comprehension of audio and visual content than written text brings in a metacognitive experience, in which a person’s experientially derived sentiments shape the response towards new information [3]. This is why people are more likely to believe false information if they are familiar with the topic of the content. Familiarity elicits a sense of fluency that makes it easier for people to assimilate new information and find it credible. Deepfake videos and images are often made around eminent personalities, that people are usually familiar with. The familiarity with the personality’s background and nature of work makes it easier for people to trust deepfakes without checking their veracity. If shared by close connections on social media platforms, the deepfake is trusted more by people due to the trust they place in their connections. The higher likeliness of images and videos to be shared on social media also increases the visibility of deepfakes and impacts the consequent exposure of the youth towards them [46].

The inability of people to discern fake facial movements of a deepfake character without sophisticated tools also makes them – particularly the youth that is most active on social media platforms – susceptible to deception by fake videos and images. Rössler et al. (2018) discovered that people could accurately identify deepfakes only in approximately 50% of the cases, which is statistically similar enough to random guessing [39]. The identification rate decreases even further if the video is compressed.

5.1. Trust erosion from digital platforms

Deepfakes can affect an individual’s perception of truth and falsity regarding digital content and can create uncertainty about the information in that content. As a result, we may witness an erosion of trust from social media, a situation where every image or video is viewed with an eye of suspicion and uncertainty. This uncertainty is technically different from ambivalence because ambivalence is the result of conflicting opinions and additional information amplifies such conflict. However, uncertainty occurs due to insufficient information and can be resolved through the supply of that information [47]. Uncertainty arises because of the high costs of acquiring accurate information, which is the case with deepfakes as well. The pervasion of deepfakes in online platforms can increase the costs of getting accurate information, thereby leading to higher uncertainty towards digital content.

A direct consequence of the spread of deepfakes on digital platforms is the reduced trust of citizens in the news on social media and videos of leaders posted on video-sharing platforms. The attitudinal outcome of deepfakes is likely to be the collapse of the trust ecosystem that gives credibility to digital platforms. This erosion of trust may occur in the backdrop of declining trust in news across the world at present and declining trust in social media globally [4]. Subsequently, deepfakes may cultivate an assumption among digital natives that a basic ground of truth cannot be established by plainly watching multimedia content on digital platforms. This can be exploited by political propagandists to sow uncertainty in digital platforms through deepfake-driven political rumors, which can eventually render digital platforms ineffective in ensuring the credibility of information. The cumulative effect of multiple contradictory, disorienting, and irrational information may generate a systemic state of distrust which can eventually drive citizens out of such platforms as they give up looking for truth on user-generated content platforms and turn to state-sponsored information in want of information.

5.2. Political microtargeting by deepfakes for radicalization of youth

The youth group – especially the age group between 14-18 years – is primarily susceptible to disinformation which can elicit violent responses from them. Deepfakes with their inherent ability of deception can have a massive influence on how the youth perceives society and shape one’s ethical values. Certain risk factors emerge as part of a young individual’s characteristics and circumstances that can influence the individual radicalization process. Adolescence is the age when individuals begin to search for their own identity [48]. During the same time, the relationship between the individual and the parents changes, because of the adolescents’ desire for independence, which makes them increasingly detach from parents and enter peer groups. This search for belonging exposes them to new avenues of information that the youth does not always verify before consumption, which leads to provocative behavior and general deviation from otherwise tolerant conduct [48]. During the adolescence period, individuals also seek adventure and provocation. The quest for knowledge and a sense of belonging eventually leads an adolescent to political socialization, which develops attitudes that remain constant over time. The youth initially experiment with different political positions, which encourages them to adopt an extremist political position and to entertain short-term changes in their fundamental positions [48]. This is further contributed to by the general frustration the youth may have about politics and the feeling of powerlessness – both are signs of political deprivation. Additionally, violent conditions at home and a lack of employment opportunities in the home country can contribute to radicalization [49]. In such circumstances, deepfakes of political leaders serve as a medium for the youth to vent their sentiments regarding politics and to display the leader in a context that aligns with the opinion of the individuals who share these deepfakes across on social media.

Dobber et al. (2019) showed that exposure to a deepfake showing a political figure significantly worsened the attitude of research participants toward that politician. Moreover, the ability of social media for microtargeting – targeting content to specific political, ideological, or demographic groups – could amplify the detriment done by deepfakes, as tailored deepfakes would be perceived as more relevant by the targeted group and would influence them more [50]. Since the youth is more active on social media, with teenagers spending an average of 7.5 hours looking at screens per day [51], it is the youth age group that is at greatest risk of exposure to synthetic media, which may get shared rapidly because of the youth’s higher susceptibility to provocation, as we studied previously.

UNESCO’s study on youth’s extremism on social media showed that digital natives, consider the internet as a natural extension of the offline society. Online actions by digital natives are sometimes viewed as equivalent to offline action, which helps to build a sense of identity formation and community building [1]. That explains why the conversations that the youth have on social media and digital forums are seen by them as reflective of the sentiment of people on the ground. The additional sense of security and privacy online aids in the dissemination of extremist, violent, and radicalized content that would not be well received by people offline [1]. Digital platforms also deliver massive publicity for the acts of extremism and enhance the perception of solidarity with extremist views, which sooner or later the susceptible youth subscribe to. The display of false information, synthetic media, and AI-generated posts on the same platform where authenticated, genuine information is posted by others, renders credibility and legitimacy to such content [1]. Consequently, the unsuspecting youth trust the content and share it widely, especially if it is posted by someone trustworthy in their network, which eventually leads to an unmoderated and uncontrolled spread of deepfakes online.

The ”liar’s dividend” is another challenge that radicalizes the youth. The deepfake-led trust erosion from digital platforms is leading to a situation where any leader can evade accountability for content related to them by dismissing any incriminating evidence as fake, which highlights the threat of plausible deniability that leaders may have in the future [52]. This can further create distrust among the youth towards their political leaders, and the dissatisfaction can translate into anti-government radicalization. As a result, the susceptibility of the youth to disinformation because of their age factor and the trust that small online communities create in echo chambers result in microtargeting of the youth and their eventual radicalization.

5.3. Sample study of deepfakes’ impact on deception and sensitization

A study was run through a global survey to understand the youth’s ability to detect deepfakes before they were revealed to be fabricated information and their sense of need for media literacy programs after the deepfakes were revealed to be false information. Using an experiment, two hypotheses were tested to understand the participants’ response towards one deepfake image and two deepfake videos – one comprising only one deepfake character and the other comprising one deepfake character with other genuine characters. Assuming that many people are incapable of detecting deepfake multimodal information, the following two hypotheses merit exploration:

H1: Individuals watching a deepfake information containing false content that is not revealed are more likely to be deceived than those to whom the falsity is revealed; and,

H2: Individuals place more importance on media literacy programs if they are deceived by a deepfake, compared to those who can detect deepfakes.

5.3.1. Research design, data, and method

Design: A representative sample (N=32) responded to three deepfake multimodal information –

- a deepfake video of American actor, Tom Cruise playing golf

- a deepfake video of American politician, Bernie Sanders

- a set of 4 images of United States past president, Barack Obama – with one of the four images being a deepfake

The characters in the videos and the image were introduced to the respondents beforehand, to ensure any unfamiliarity with the characters does not hamper their judgment. The survey on the first deepfake video (of Tom Cruise) was followed by an educational video on deepfakes using a synthetic video of Morgan Freeman talking about the risk of deepfake-driven disinformation, followed by the survey on the second deepfake video (of Bernie Sanders). Finally, the participants were asked about their affinity to consuming news online and their perception of the effectiveness of media literacy programs on the topic of deepfakes.

Treatment: Existing deepfake videos of renowned celebrities were used to ensure participants are exposed to information that is available in the public domain. The first deepfake video of Tom Cruise shows him playing golf and interacting with the viewers in a short under-1-minute video. Next, the participants are asked if they found Tom Cruise to have played the shot well or poorly, or if they did not believe it was the Tom Cruise they knew of. The options were purposely crafted to understand if the video invokes positive, negative, or neutral reactions in the minds of the participants, or if it comes out as a deepfake.

The next deepfake video showed Bernie Sanders dancing with a troupe and participants were asked about their perception of Bernie Sanders as a presidential candidate. Only one option allowed them to notify that the video seemed far from genuine. Both the videos allowed participants to also register their response as “Can’t say” because of a neutral judgment of the videos despite being unable to detect them as deepfakes. The survey purposely administered a deepfake video of a political personality and a non-political personality to understand if the perception created by deepfake videos is different based on the field of work the personality belongs to.

Finally, the participants were asked to identify one deepfake image of Barack Obama in a set of 4 images of the same person. This process was undertaken to understand if participants displayed a comparable magnitude of deepfake detection capability with still images, instead of moving videos.

Measurement of variables: To see if the participants could identify the deepfake, we directly asked them about their perception of the personality in the video/image and checked if they showed any indication of doubt regarding the authenticity of the content. Participants who responded with options mentioning a neutral perception of the information were also considered to have been deceived by the deepfake since they could not identify with certainty the falsity of the information presented. Participants who responded with having positive or negative perceptions of the personality in question were also treated as deceived individuals. The difference between the number of participants detecting the first and the second deepfake video was used (H1) and the number of deceived participants showing positive perception towards media literacy was used (H2).

5.3.2. Participation and Analysis

Participants: The treatment was administered to a sample of global respondents, with a survey form shared in digital platforms having members from multiple nationalities. Compared with lab-based experiments, experiments embedded in online surveys offer greater representativeness and enable rich and realistic treatments [4]. As the online questionnaire was self-administered, responses were less affected by social desirability biases which is required for studying disinformation [4].

Procedure and responses: The questionnaire included 2 questions asking for feedback on the two deepfake videos, 1 question on a set of 4 deepfake images, and 4 questions on consumption of online news, platform usage, and perception towards media literacy programs. All participants responded to all questions, as they were all made mandatory.

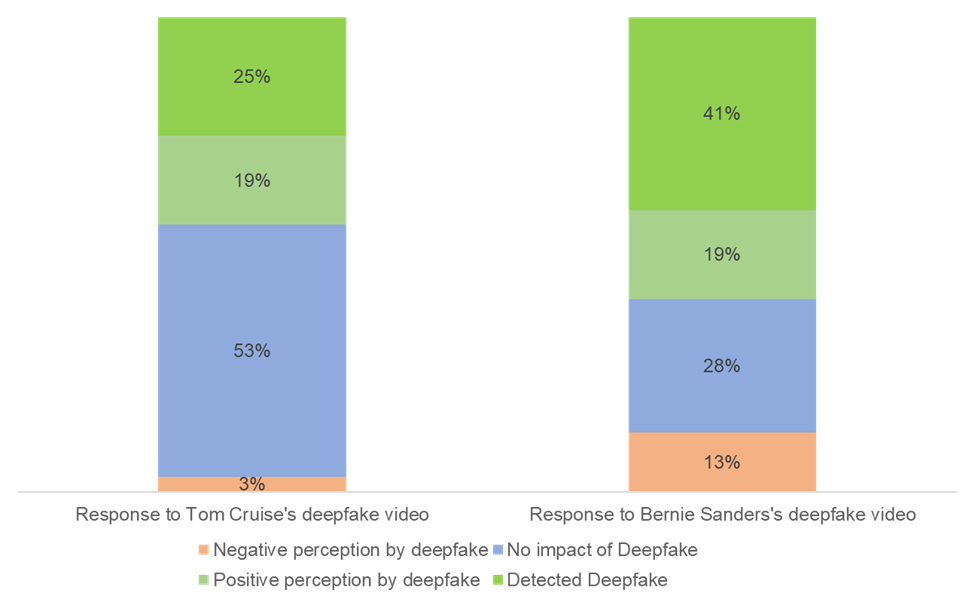

Analysis: Only 26% of the participants could successfully detect the deepfake video of Tom Cruise, while 52% of the respondents had a neutral reaction towards it. More (19%) deceived participants had a positive perception of Tom Cruise’s sports skills compared to a negative perception (3%). Following the educational video on deepfakes, the detection rate of the deepfake video of Bernie Sanders increased by 13% and 39% of the participants could successfully detect the video as a deepfake. People who had a neutral response to Sanders’ video decreased to 29% and participants with negative perceptions increased to 13%. The number of people forming positive perceptions after watching a deepfake remained the same at 19%. Figure 2 presents the results of the survey to highlight how the two deepfake videos influenced the perception of the participants.

Fig. 2: Assessment of deception participants by deepfake videos of eminent personalities, by treatment

Surprisingly, the revelation of deepfake videos could help the participants in detecting a deepfake still image. None of the participants could identify the deepfake image of Barack Obama in a set of 4 images. This highlights that individuals who may be capable of detecting deepfake videos by noticing subtle signs of falsity in the in-video movement of characters, may not be able to detect a deepfake image due to close similarity of deepfakes to original still images.

The data shows how deepfakes create a more negative perception of political personalities while reducing the magnitude of neutral perception towards them. It highlights that people are more driven to form judgments on either the positive or negative side after being deceived by the deepfake of people in politics. Overall, the first hypothesis (H1) that the number of participants getting deceived by deepfake videos before falsity is higher than those to whom the falsity is revealed stands validated.

To test the second hypothesis, a Chi-Squared test was conducted to understand the relationship between the incidence of deception of an individual and the individual’s outlook toward the need for media literacy intervention. Chi-squared test was chosen because the dependent variable, i.e., the incidence of deception is categorical. Table 1 shows the outlook of participants towards media literacy intervention after watching the two deepfake videos and one deepfake image and following the revelation of falsity of information in the deepfake videos.

| Outlook towards relevance of media literacy interventions after watching deepfake videos | |||||

| People’s response to deepfake | Very helpful | Helpful | Neutral | Not very helpful | Not helpful at all |

| Negative perception by deepfake | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| No impact of Deepfake | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Positive perception by deepfake | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Detected Deepfake | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 25 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 1: Relationship between incidence of deception and perception of the need for media literacy intervention

The chi-squared test resulted in a p-value of 0.089, which is above 0.05 and therefore, the test result is not statistically significant. This implies that not sufficient evidence exists to say that there is an association between the incidence of deception by deepfake and a sense of need for media literacy intervention. As a result, the second hypothesis (H2) stands rejected and implies that regardless of one’s capability to detect deepfakes, individuals generally perceive media literacy interventions to be of high useful.

5.3.3. Limitations

The availability of the deepfake videos and images in the public domain could have influenced the responses of a few participants because of the pre-survey knowledge they carried about the deepfakes. The knowledge of a particular deepfake video or image beforehand could have masked the inability of the informed participant to detect deepfakes. For the sake of simplicity of the research survey and to respect the anonymity of the respondents, no second-level check was done with them to understand if they were already aware of the deepfake information presented in the survey.

- Role of Education and Digital Media Literacy

Media literacy programs – in their current versions and future editions – hold a possibility to equip digital natives with the knowledge of deepfake detection, trust establishment in digital platforms, and proactive reporting of disinformation. This requires the digital natives to understand the techniques of detecting deepfakes with or without advanced AI-based synthetic media identification tools. Various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of media literacy programs in increasing awareness and the tendency to verify digital content before reacting to it. Empirical evidence on the effectiveness of digital media literacy campaigns is sparse, yet existing research shows that such programs can improve an individual’s ability to navigate the information environment online. Digital media literacy interventions have also been found to increase the individual’s discernment between genuine and fake news [54], which is crucial for preventing the amplification of multimodal disinformation. This is especially important for out-of-context visual disinformation, where altered images and videos have an indexicality (true-to-life impression), thereby adding evidence to the claims made in the visuals [53]. Since images are viewed as a more direct representation of reality than text, media literacy assumes importance for the youth to prevent any attitudinal or behavioral change in response to the persuasive power of the visuals.

Detecting deepfake-based synthetic media at an early stage helps to combat the engagement with and spread of visual disinformation. Media literacy programs for the youth aim to enable them to identify disinformation to deter its retransmission on online networks. This is critical for visual content, as visuals tend to be associated with a greater degree of persuasion and engagement. For example, Coe et al. (2020) found that tweets with images receive 89% higher likes and are retweeted 1.5 times more often than tweets without images [55]. Media literacy programs hold significance in increasing the accuracy of identifying out-of-context visuals, as it stood at 66% in a study by Luo et al. (2021) where participants were asked to distinguish between genuine and falsified image-caption pairs [56].

6.1. Impact of digital media literacy efforts

Digital media literacy contributes to the skills and knowledge that individuals need to critically navigate their online multimodal media environment. Empirical evidence has documented a positive impact of digital media literacy and the acquired ability to discern genuine and false information. For example, Shen et al. (2019) included participants’ internet usage skills, social media use, and photo editing experience in digital media literacy and found in their study that individuals with a higher degree of digital media literacy performed better in evaluating the credibility of images [57]. Similarly, Hargittai et al. measured digital literacy as an understanding of various internet-related terms and found it correlated with individuals’ ability to locate accurate information in an online environment [58].

The underlying premise of digital media literacy interventions is the Deficit Hypothesis which posits that individuals who are susceptible to false information do not hold sufficient knowledge to distinguish between genuine and false information [59]. Media literacy interventions help people acquire critical thinking skills for identifying disinformation by educating them about the information production process and the impact that information may have on society. Such interventions also enhance people’s ability to correctly assess message credibility by bolstering the perceived information credibility of genuine content, while reducing the same for false information. This happens through an increase in knowledge and self-efficacy while diminishing risky and anti-social behavior [60]. This leads to a higher ability to discern between mainstream and false news using certain indicators.

However, the effectiveness of such digital media literacy programs depends on the design of the literacy messages, especially if they are not adapted to the online media environment. Vraga et al. found that exposure to news literacy programs increased cynicism toward information [61], which highlights the potential drawbacks of poor design of media literacy programs. Individuals may view news and mediated information with higher skepticism, following the administration of media literacy interventions. Another challenge with digital media literacy programs is that discernment tends to be specific to the context and domain, and therefore, shows a short-term efficacy [53]. Most studies have not analyzed the long-term efficacy of literacy interventions in fostering critical media assessments.

Deepfake-specific literacy is required for such interventions to be successful in the times of GenAI-fueled synthetic media. While general media literacy is found to be effective in reducing the persuasiveness of and intention to share visual disinformation, visual-specific literacy is required for detecting visual manipulations in multimodal disinformation [62]. Reverse image search is an effective method to check the credibility of images. Hameleers et al. showed that individuals’ political inclination also plays a role in the determination of message credibility and belief in disinformation, even after exposure to the correction of the disinformation. Social media use behavior is also associated with the critical consumption of information in digital media platforms [53].

Therefore, an individual’s social media use, political inclination, skepticism towards media, visual literacy, and deepfake-specific literacy will be covariates in assessing the effectiveness of media literacy interventions.

6.2. Recommendations for enhancing digital media literacy interventions

Potter (2014) advocated certain methodologies and guidelines for the administration and monitoring of media literacy interventions in the digital age. The three methodologies studied in the research work are Naturalistic Intervention, Educational Evaluation, and Social Scientific Studies. Each method has its own set of agents, treatments, and outcomes for transmitting digital media literacy among the youth [64].

Naturalistic interventions are delivered by individuals in the course of their daily life, as and when opportunities arise for the interventions to cope with certain media messages. This method is restrictive as it prohibits an individual from using certain types of media to limit exposure to certain pieces of disinformation. However, the effectiveness of a naturalistic intervention is dubious as it is associated with lower positive attitudes towards the prohibitor and higher positive attitudes towards the content and entities sharing the disinformation [64]. This motivates the youth to violate the intervention and consume the disinformation content with higher curiosity. Social co-viewing is a type of naturalistic intervention where the intervention agent (for example, a parent) and the target consume information together to ensure no exposure to disinformation occurs. However, co-viewing is becoming a rarity because of the busy lifestyle of adults, leading to the youth consuming content solitarily.

Educational evaluations involve a group of educators who design and implement a series of treatments in a formal, live setting. These include small-scale classroom sessions or large-scale curriculum design for country-wide educational institutions. Such interventions help to standardize the method of media literacy programs but also involve several agents to develop the curriculum [64]. This becomes a challenge because of the different outcomes that different agents want to achieve which leads to the consumption of time in resolving differences of the agents and synthesizing diverse opinions into a coherent curriculum. Few organizations have implemented this method. For example, Flashpoint was developed as a teaching module to help children and adolescents become active thoughtful consumers of media information and resist impulses for violent extremism. Coping and Media Literacy was designed for children aged 7 to 13 to learn with their mothers about how to deal with terrorism-related messages in media messages. The educational evaluation method is beneficial for the target audience.

Social Science Studies-related intervention treatments are designed by scholars and researchers who focus on a couple of characteristics of media messages. Through this method, they intend to reduce the complexity of media influence to analyze a particular factor and its effect on the youth in greater detail [64]. The output is generally basic knowledge about the influence of media on the targeted youth.

Potter (2014) suggests 7-step guidelines for designing media literacy interventions in the future.

- The process begins with a clear conceptualization of media literacy and differentiating it with solely critical thinking.

- Next, the learning objectives need to be determined, as the objectives help in the assessment of the performance of the intervention. The intervention design needs to clearly state the type of change it intends to drive among the targeted youth. Any expectations on alteration in attitude, emotional reaction, behavioral pattern, and ideologies need to be identified.

- Third, the scope of the intervention is to be determined. The target audience for the intervention has to be analyzed comprehensively by the agent to understand if the media literacy efforts would be of any value to the target. A pilot test with a segment of the target audience can help refine this understanding.

- Fourth, the treatment has to be designed to meet the specific real needs. As part of the intervention, those messages have to be selected that have the highest potential to influence the target. The design of the treatment must be comprehensible to the target across all age groups, educational backgrounds, and other demographic factors.

- Fifth, train the agents to implement the intervention and administer the program. Implementation can become a challenge if the target is spread across different geographical regions.

- Sixth individual post-treatment outcomes need to be measured and fed into the process through a backward loop, which helps the process to improve iteratively with each implementation.

- Finally, the intervention needs to be analyzed to check which youth in the target group do not display the intended change and how far the program is from the objective.

This methodology can act as a guideline for the design of potential media literacy interventions to educate the youth on deepfakes, their challenges, and ways to mitigate them.

- Legal and Policy Implications

Policy action is required by countries to contain the negative consequences of generative AI-fueled deepfakes. Few countries and economic unions have begun taking an active interest in framing regulations to oversee the use of AI technologies in diverse sectors. The European Union (EU) has taken a major step in passing one of the world’s first laws for governing the use of AI and for setting a global standard for I-based technologies, including deepfakes [65]. The proposed law also requires generative AI technologies, such as ChatGPT, to comply with transparency requirements which include disclosure of the content generated by AI, design of models that prevent the creation of illegal content, and publication of summaries of copyrighted data used for training [66]. The European Union also updated its Code of Practice on Disinformation in 2022, which aims at checking the spread of disinformation through deepfakes. The establishment of the High-Level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation, The Communication on Tackling Online Disinformation, and the Public Consultation on Fake News have been positive steps in this direction. The second one recommends the creation of a multi-stakeholder forum to examine the applicability and challenges of EU regulations on generative AI applications. It also advocates for the creation of an independent network of Europe-based fact-checkers and the launch of a secure European online platform related to awareness of disinformation [67].

The United States has introduced a bipartisan Deepfake Task Force Act to assist the Department of Homeland Security in countering deepfake technology. A bipartisan bill in the United States, the Honest Ads Act, requires companies to disclose details of the political advertisements placed on their platforms [67]. China has introduced a comprehensive regulation on deep synthesis, which has been effective since January 2023. It requires clear labeling and traceability of deep synthesis content, along with mandatory consent from participating individuals. Germany has the Network Enforcement Act that imposes penalties of up to 50 million Euros on social media companies that fail to remove the “obviously illegal” content within 24 hours of receipt of a complaint. Similarly, Indonesia and the Philippines have also taken a legal route to mitigate disinformation online.

Few countries have chosen the route of non-legislative measures. For example, Malaysia has launched an information verification website, sebenarnya.my, to counter fake news [67]. Qatar has introduced the “Lift the Blockade” website to mitigate disinformation campaigns. Media literacy programs have been introduced for school students in Canada, Italy, and Taiwan. Italy has mandated that all individuals who start an online publishing and information disseminating platform notify the territorial tribunal of their platform name, Uniform Resource Locator (URL), name of the administrator, and tax number [67]. A few countries, such as India, are still awaiting legislation on deepfakes and disinformation. However, Section 500 of the Indian Penal Code provides punishment for defamation, and Sections 67 and 67A of the Information Technology Act (2000) have provisions that can be applied to certain aspects of deepfakes and disinformation.

7.1. Responsibility of digital platforms and social networks

Internet intermediaries share a responsibility in the mitigation of disinformation through deepfakes. The absence of regulations against generative AI-fueled deepfakes and disinformation in general traditionally shields for-profit organizations from their responsibility for the acts committed on their platforms. Because of a lack of strong incentives and an imperative, digital platforms evade the responsibility of taking independent action against disinformation. Social media organizations show hesitation in making their data available to social scientists for research, which inhibits analysis of the impact of deepfakes and the resulting disinformation on consumers of that information. Policymakers need to encourage technology companies to broadly disseminate their data to social scientists through responsible and privacy-preserving platforms.

Digital natives also share a responsibility to stay vigilant while consuming information on digital platforms. Ali et al. (2021) describe a practical model using the Educational Evaluation method to teach children in schools about deepfake and disinformation. Using a schoolbook app simulation, students participating in the study were taught how to identify features of disinformation that incite emotions, polarization, and social division [68]. Simulating the spread of disinformation with neutral information, and subsequently enabling the students to self-reflect helped them to identify the cues they had missed in detecting disinformation in the messages passed on to them. In the final phase of the research workshop, the students were educated in a classroom setting about policies against deepfakes and disinformation. Such educational programs need to be emulated for people across all age groups, educational backgrounds, and socioeconomic groups because of the pervasiveness of disinformation in digital platforms.

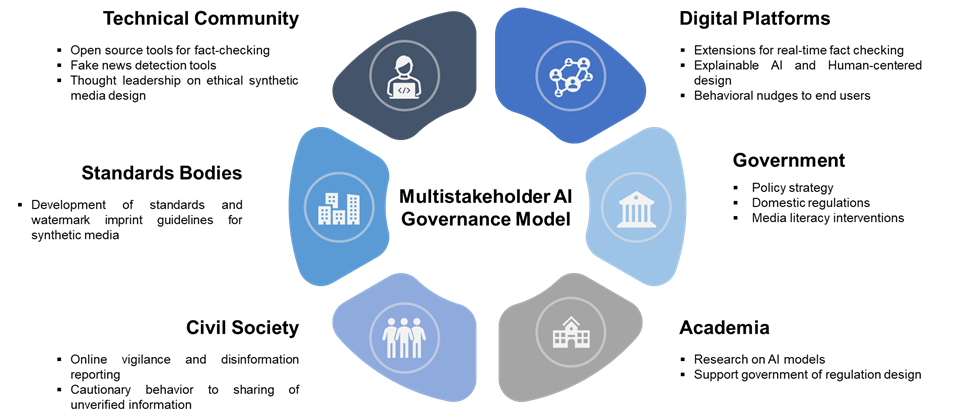

7.2. Multistakeholder approach to policy formulation

The solution for mitigating disinformation by generative AI-fueled deepfakes requires broad-based efforts across governments, academic institutions, private organizations, and civil societies to translate breakthroughs in AI with widespread benefits. This requires the institutionalization of a participative AI governance process for all the involved stakeholders. A multistakeholder approach to AI governance can allow the development of common standards and the sharing of best practices that can be instrumental in formulating proportional, risk-based regulations [69]. Incorporating viewpoints of diverse stakeholders can also ensure the development of co-regulatory solutions that can increase the inclusion of non-majoritarian perspectives for bringing pluralism to the generative AI governance models.

Digital platforms, such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter need to become partners in monitored self-regulation and co-regulation with the government and other public institutions. This would entail that the digital platforms, including social networks and search engines, include extensions for real-time fact-checking which are developed in-house or by third-party software providers [67]. The news publishing and content-sharing companies must allow users to choose from a catalog of fact-checkers and display the average rating of veracity provided by them. Organizations like Poynter, PolitiFact, the Ethical Journalism Network, and Snopes offer such ratings related to content verification, based on the inputs given by data scientists, AI models, and experienced human journalists [67]. Enabling such extensions on major internet browsers is a possible step towards fostering multistakeholder cooperation. Corrective information that is presented by the fact-checkers can be regarded as an effective rebuttal of online disinformation on digital platforms [63]. The integration of the simplicity of the message with factual information can be an effective strategy to counter falsehoods online [63].

As equal stakeholders in the generative AI governance model, the governments of the world need to include a more proactive media policy to counter online disinformation. This is because simply advocating greater control over disinformation on the side of digital platforms would not solve the issue of polarization and falsity in the information shared online [67]. Advocating the notion of neutrality for search engines and social media platforms would inevitably translate into a display of the majoritarian content in the most prominent spaces because of the higher volume of search around those majoritarian topics, which can eventually sideline the niche and local content [67]. Therefore, a media policy strategy is required to be put in place to counter polarized, unverified content on digital platforms, despite its conflict with the concept of absolute internet neutrality.