Here’s an essay critiquing the dominance of English, written in English itself. Isn’t that an irony? The insurmountable dominance of English in academia is evident in the way we argue about it in the very same language. Undeniably, there are genuine reasons why scientists, scholars, and the academic community think, work, and collaborate using the symbols of the English language. Despite the proliferation of Arabic and Latin as the media of communication among scientists in the pre-World War era, World War 2 tilted the axis of scientific communication towards English. The surge in the volume of research publications in the United States and other English-speaking countries, and the consequent purge in research literature authored in non-English languages have positioned English as the dominant language for science communication.

Having English as the ‘hyper central’ language in scientific academia has several advantages for researchers globally. Since an overwhelming majority of scientific journals worldwide accept manuscripts in English, authoring papers in English offers a far wider platform for researchers to publish their work, compared to what vernacular languages can provide. These journals act as platforms where two groups – published authors, and publishing authors – interact virtually for literature reviews. The two-sided network effects (Caillaud and Jullien, 2001) ensure that the growth in the number of published authors in journals leads to growth in the number of researchers who would cite them. Publishing in a language other than English would result in the researcher missing the opportunity to increase citations, which builds reputation. Not to forget, the previously published research papers that inform a researcher’s work are also mostly in English, resulting in the researcher using English to document the literature review. Moreover, authoring papers in English facilitates the discovery of one’s research by other researchers globally, which can increase visibility, recognition, and opportunities to collaborate with better institutions that can offer better funding for the research. Such discoverability expands one’s professional network, helping one to find cross-border collaborators and funding opportunities.

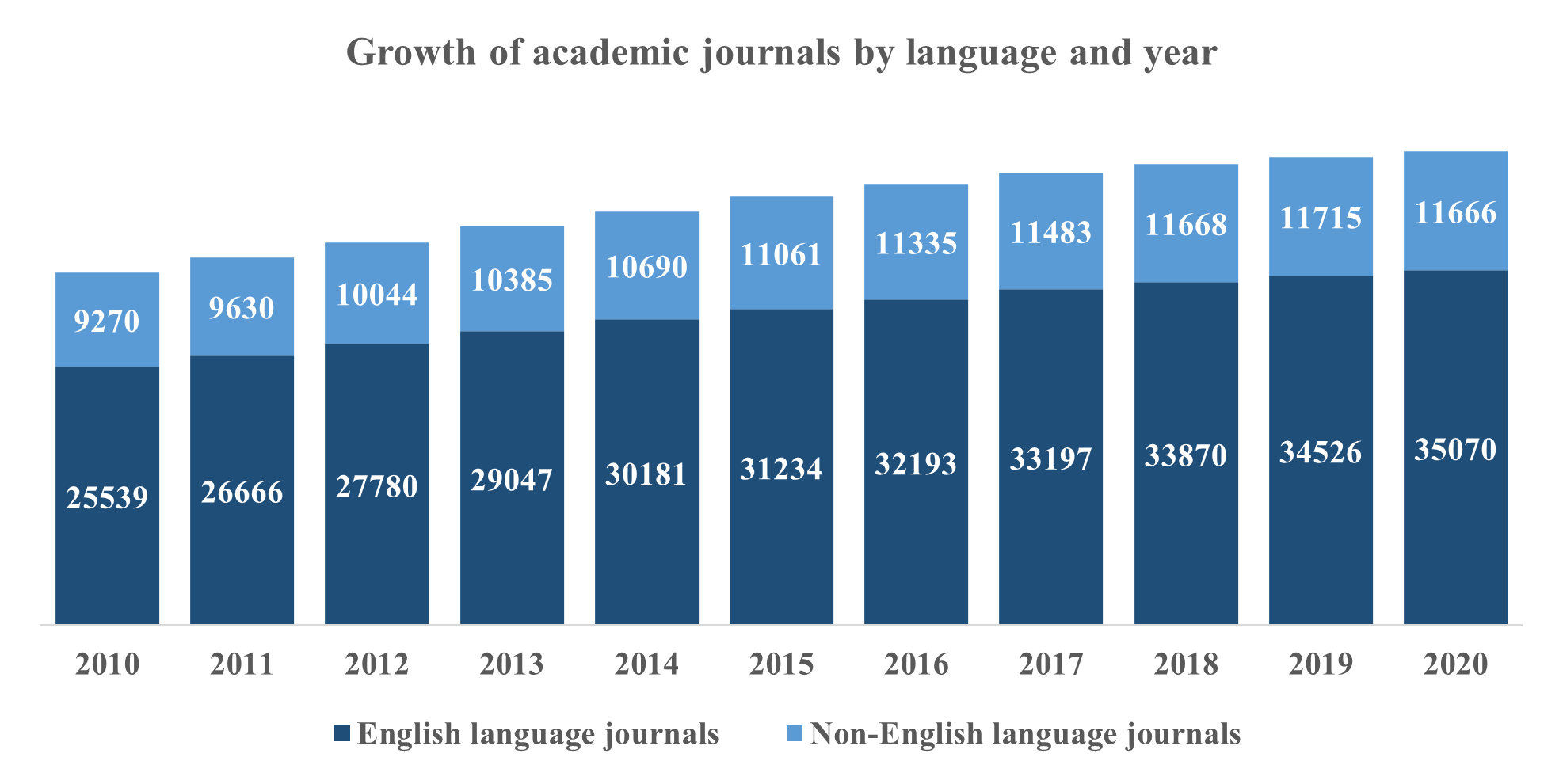

Since academicians and researchers search for credible information online using search engines that accept queries in English and produce better results in English, it makes better sense for a researcher to use English for authoring a research piece to enjoy greater global discoverability. Furthermore, most reputed journals depend on a peer review system to evaluate the suitability of research articles for publication. English’s pervasiveness simplifies the process of peer review and evaluation because it establishes a common language for communicating research findings and methodologies. Standardized communication enhances transparency and reproducibility in scientific research, contributing to the advancement of knowledge across disciplines. The use of English as the medium of instruction and science communication in school also makes people more comfortable in expressing their scientific thoughts in English, as they can effectively carry the lessons from their school and college to their field of research. Even scholarship and fellowship opportunities offered by institutions have interviewers and evaluators who have published scientific findings in English, making them more proficient in assessing an applicant’s English-based research than the ones in the vernacular language. Figure 1 illustrates the growth in the volume of academic journals in English compared to the smaller volume of non-English language journals.

Figure 1. Growth of academic journals in English and non-English language by year (Source: WordsRated)

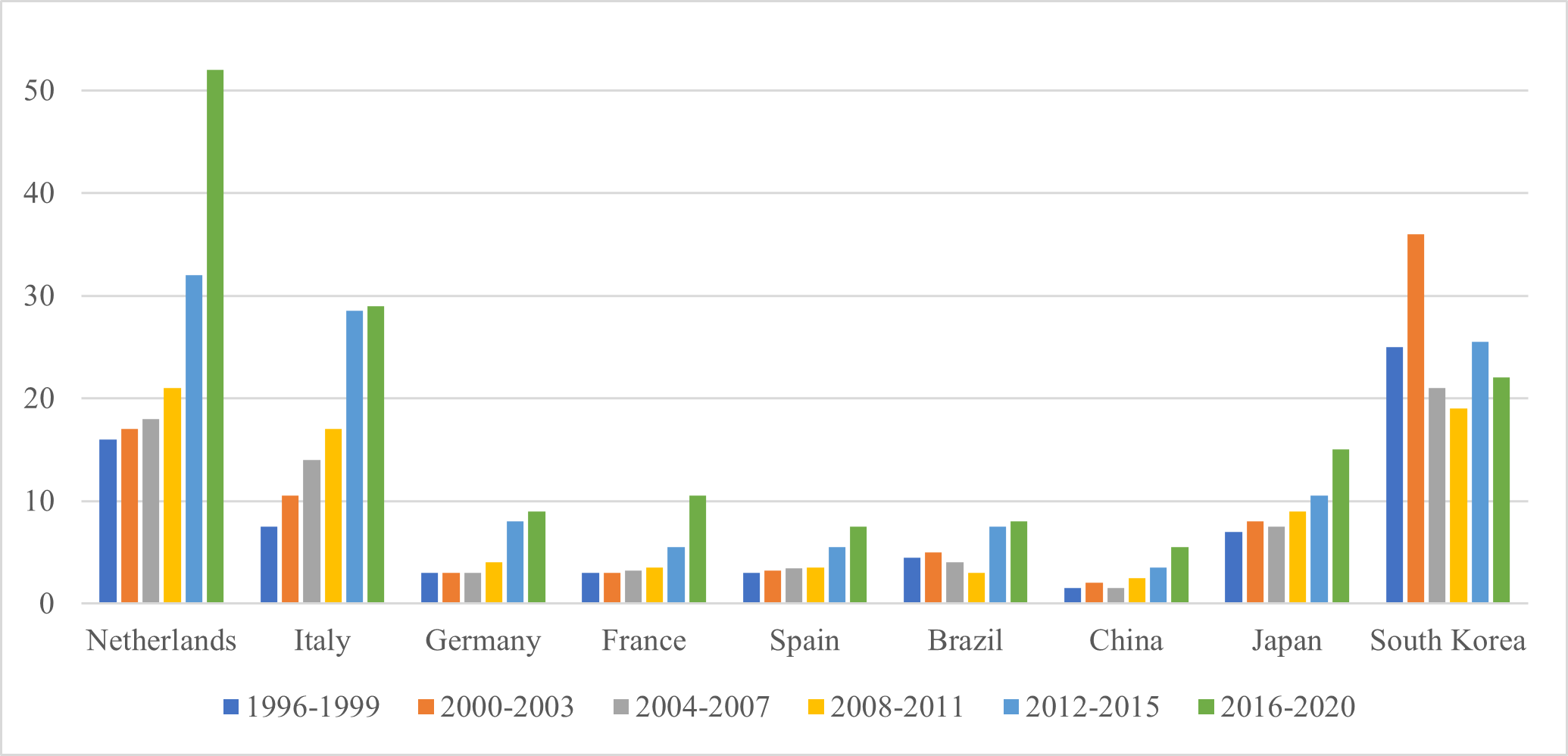

English also allows researchers across linguistic and ethnic diversity to access a vast repository of scientific literature, enabling them to stay updated on the latest scientific developments. It promotes inclusivity by providing equal opportunities for scientists and scholars from non-English-speaking countries to publish in renowned journals, participate in international conferences, and engage in global research projects. Figure 2 illustrates the meteoric growth of journal articles written in English as a ratio of articles written in the concerned country’s official language.

Figure 2. The ratio of journal articles published in English to those published in the country’s official language (Source: Elsevier)

However, the hegemony of English in academia has its downsides too. The linguistic imperialism perpetuated by English marginalizes other languages in the scientific community. Consequently, the dissemination of ancient and modern knowledge preserved in non-English languages gets affected, thereby impeding the visibility of research conducted in non-English-speaking regions and hindering globally inclusive exchange of ideas. Using English in primary and secondary schools for teaching science indoctrinates people to think and communicate science in a monolinguistic fashion. The monolingual approach to knowledge production and preservation limits the scope of scientific inquiry, perpetuates socioeconomic and professional inequities among non-English-speaking researchers, and erodes traditional ways of knowing about the universe. It creates a massive barrier to studying and citing traditional knowledge that has been preserved in scriptures and manuscripts older than the advent of English.

Databases and citation indices of prestigious international journals are replete with those published in the English language (Hamel, 2007). Moreover, programming languages used by the researchers for analysis and modeling are based on English phrases and words. Text generation capabilities and outputs by artificial intelligence technologies are also based in English. This limits the scope of scientific discourses that marginalized communities can have on various platforms. Translation of existing research publications into vernacular languages is offered as an alternative but has the downside of high cost and can result in a linguistic hierarchy with English at the top from which information in other languages flows.

Therefore, while English’s dominance offers numerous advantages of facilitating communication, collaboration, and access to knowledge, it does call for immediate steps to foster linguistic equity, cultural diversity, and inclusivity. Efforts to promote multilingualism, language diversity, and equitable access to scientific information are essential for fostering a truly inclusive and equitable research environment.

References:

- Caillaud, B. and B. Jullien (2003). Chicken & egg: Competition among intermediation service providers. RAND Journal of Economics 34, 309–328.

- Hamel, R. E. (2007). The dominance of English in the international scientific periodical literature and the future of language use in science. AILA Review 20(1):53-7. https://doi.org/10.1075/aila.20.06ham